By Dare Akogun with Agency Reports

The Convention on Biological Diversity, or CBD, is an international treaty established at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, along with two other multilateral agreements: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

As with those conventions, the CBD is governed by a Conference of the Parties, or COP.

The main objectives of the CBD are:

The conservation of biological diversity.

The sustainable use of its components.

The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits of genetic resources.

To date, 196 countries have ratified the CBD and are thus parties to the convention.

The US is a notable outlier, as the only UN member state not to have ratified the treaty – although it still has a presence at COPs.

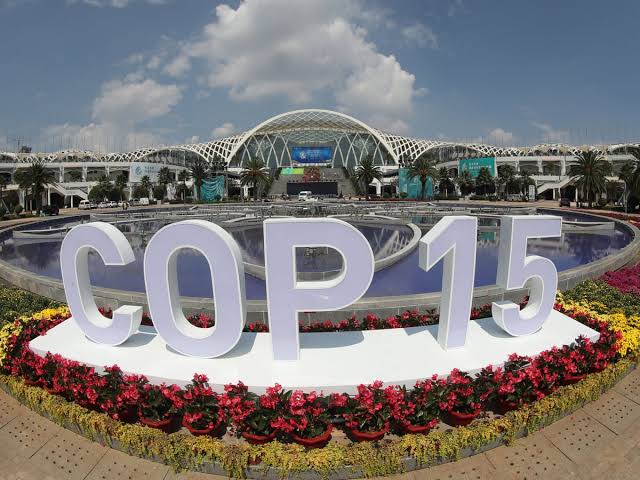

COP15 will also urge parties to set new progress on the CBD and to deliver an implementation plan and capacity-building mechanisms on the agreements that make up the convention.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety is dedicated to protecting nature from the risks posed by living modified organisms, while the Nagoya Protocol provides guidance on access to genetic resources and the fair sharing of its benefits.

The Cartagena Protocol also includes a “Supplementary Protocol” that provides rules on liability and redress relating to living modified organisms.

Originally, COP15 was due to take place in Kunming, China in 2020, marking the first time the country would hold a major UN environmental conference. The summit was postponed several times due to the Covid-19 pandemic and was ultimately split into a two-part affair.

The first part of the conference was held in October 2021 as a hybrid event both in Kunming and online. That meeting resulted in the Kunming Declaration, a non-binding agreement reaffirming the parties’ commitment to upholding the CBD.

While the second part was initially supposed to be held in Kunming in late April and early May 2022, it was ultimately moved to Montreal, Canada from Dec 7 – 19 due to continuing Covid-19 restrictions – although China still holds the presidency of COP15.

In between the two halves of the COP were three meetings of the open-ended working group, including the final working group meeting which is set for 3-5 December, immediately before the COP begins.

Carbon Brief has reported on the progress made in the previous meetings in Geneva and Nairobi.

What is the ‘post-2020 global biodiversity framework’?

The overarching goal of the global framework, which is intended to be finalised by the end of COP15, is to reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

Decadal goals for biodiversity were previously set at the CBD’s COP10 in 2010, which was held in Nagoya, Japan. At that summit, almost every country in the world formally adopted the UN’s Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-20, agreeing to 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets in order to achieve a goal of “living in harmony with nature” by 2050.

These targets aimed to at least halve the loss of natural habitats, eliminate subsidies that are harmful to biodiversity and expand nature reserves to cover 17% of the world’s land areas and 10% of marine areas.

In September 2020, a CBD report found that governments had collectively failed to meet even a single one of these targets.

But the report cautioned against losing momentum, saying that “it is not too late” to “bend the curve of biodiversity decline”. It added that doing so will require actions consistent with the targets in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement.

At the biodiversity COP14 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt in 2018, parties decided to develop the post-2020 GBF and create a “dedicated open-ended intersessional working group” to help with its preparation.

The first draft of the framework was published in July 2021, after two rounds of pre-pandemic, in-person meetings and one round of virtual meetings of the working group and the CBD’s technical and implementation bodies.

The most recent draft of the text was finalised after the fourth meeting of the working group, which was held in Nairobi in June this year.

The GBF as it currently stands builds on the past decade’s Aichi targets and Strategic Biodiversity Plan. The text has 22 targets and 10 “milestones” for how to get there by 2030, en route to the overarching goal of “living in harmony with nature” by 2050.

There are more than 900 square brackets in the GBF ahead of the Montreal talks. Items in these brackets are still up for discussion and have not yet been agreed between countries. A text is not finalised until nations reach a consensus and remove the brackets, settling on a final wording around each issue.

What are the key negotiating groups at COP15?

The key players at UN biodiversity talks differ from those at UN climate negotiations.

Notably, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) – a powerful force at climate summits – does not have a strong voice at biodiversity summits. The Group of 77 (G77) plus China, which was instrumental in the set-up of the historic loss-and-damage fund at COP27, also lacks a significant presence.

The African Group, however, does operate in a similar way at biodiversity talks as it does at climate talks. At COP15, it is seeking to balance ambitious goals with the need for development. The EU is also a major force at both climate and biodiversity summits.

Other major groupings include the Like-Minded Mega Diverse Countries (LMMDs) – a group consisting of Bolivia, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Malaysia, Peru, Philippines, South Africa and Venezuela. This group looks after around 60% of the world’s biodiversity.

(The LMMD group has been less active at biodiversity summits in the last few years, an expert tells Carbon Brief. In Geneva, a new grouping called the Like-Minded Developing Countries on Biodiversity and Development – including the African Group, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, India, Pakistan and Venezuela – issued a joint statement demanding $100bn a year for biodiversity.)

Major economies find a home in JUSCANZ, a group representing Japan, the US, Switzerland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In Nairobi, this group issued a statement opposing demands for a new, ring-fenced global biodiversity fund. (It is likely the UK will join this group now that it has left the EU.)

Indigenous voices operate at the CBD through the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity (IIFB). Reflecting the importance of Indigenous knowledge and rights at biodiversity summits (see: Indigenous rights), this group actively participates in discussions on documents and draft decisions – and is able to give statements during plenary sessions.

Other regional groups that sometimes intervene in negotiations include the Latin America and Caribbean Group (GRULAC), the Asia-Pacific Group, the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) and the Central and Eastern Europe group.

It is worth noting that, in general, interventions by negotiating blocs are less coordinated at biodiversity summits than they are at climate summits, experts tell Carbon Brief. For example, some LMMDs, such as Costa Rica and Colombia, are pushing for an ambitious outcome at COP15, while others, including Brazil, have historically been seen to block progress.

There are also major country groupings that are helping to shape negotiations on the GBF.

The High-Ambition Coalition for Nature & People, co-chaired by Costa Rica and France, is a group of 114 nations that have pledged to protect 30% of the world’s land and sea by 2030 – one of the flagship targets of the GBF (see 30×30).

The Global Ocean Alliance (GOA), led by the UK, is a group of 73 member nations. 132 nations have pledged specifically to protect 30% of their oceans by 2030.

Source: www.carbonbrief.org